First Avenue, Seattle: a photo documentary/oral history project and five-part radio series

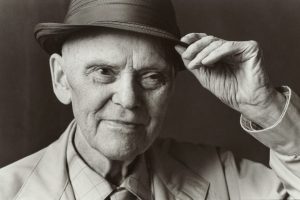

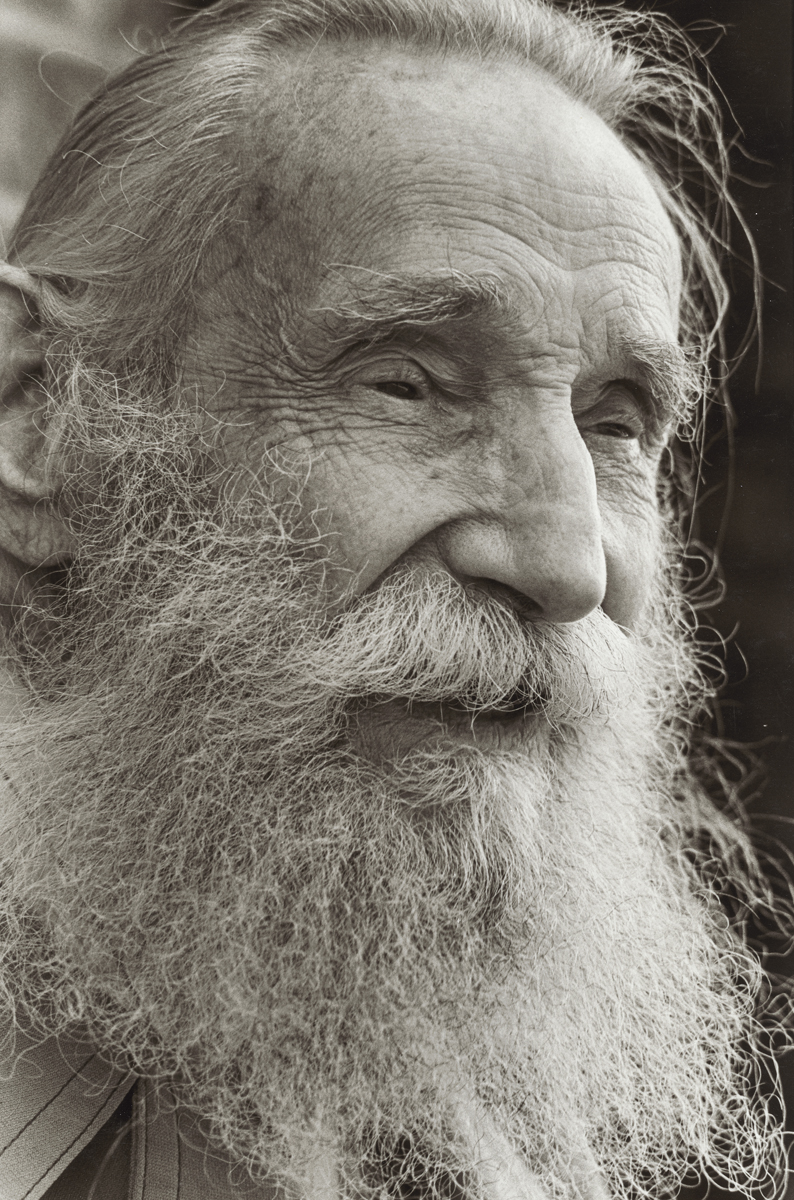

Olger Barman arrived in Seattle from Norway as a young man in 1910. The waterfront was “covered with the masts of sailing vessels – schooners carrying lumber to Hawaii, Mexico, Peru, Australia.” Looking for logging work, he asked where all the working stiffs stayed. The bus driver directed him to the cheap hotels, dance halls and saloons of First Avenue. Decades later he remembered the sight of a lovely prostitute on a hotel balcony with a megaphone: “She’d just pull the robe open and throw her hair back and say, “This way, boys! Any ol’ way you like it. Three-way for a dollar, white, yellow or black.”

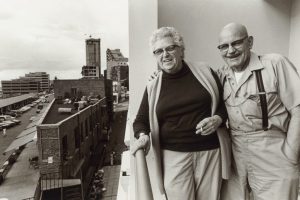

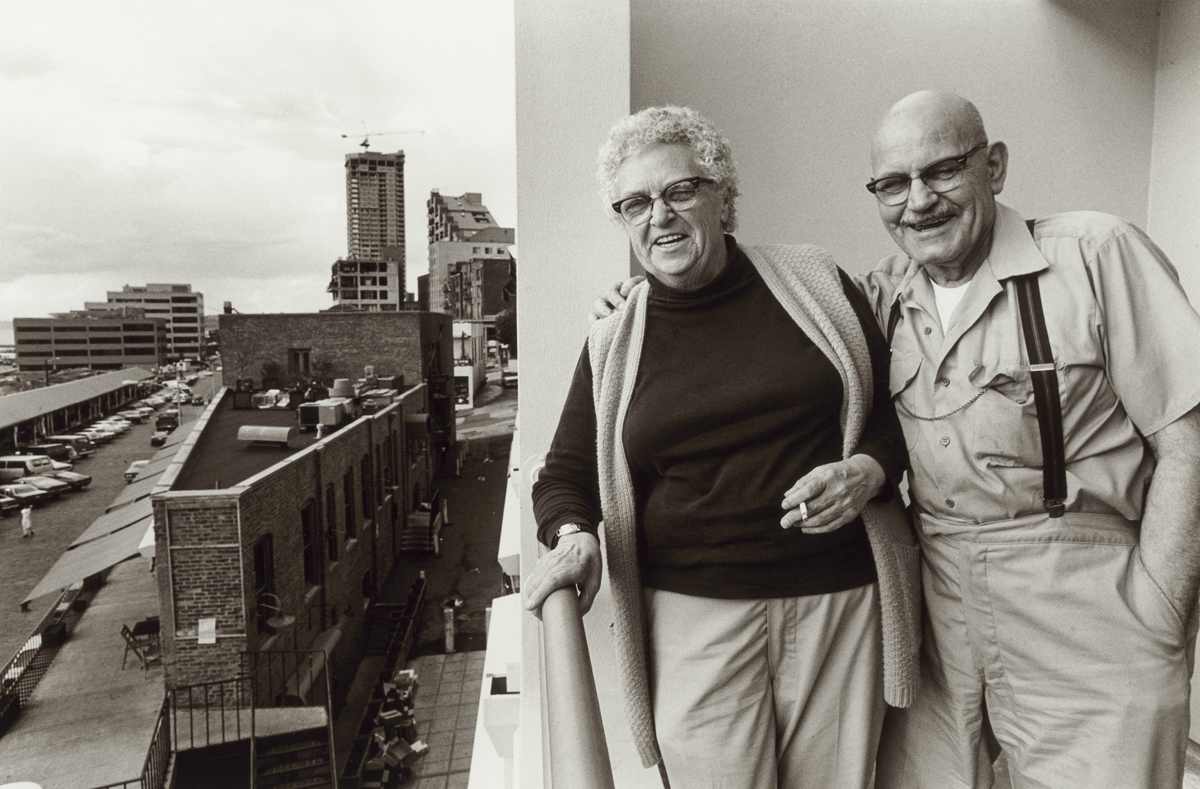

Mabel and Jesse Petrich, who lived in the Sanitary Market Apartments overlooking Pike Place Market, remembered the area’s heyday: “Hell, First Avenue used to be bouncing till two or three in the morning. There were bars and cathouses, every hotel had a red light over the entrance. Christmas!”

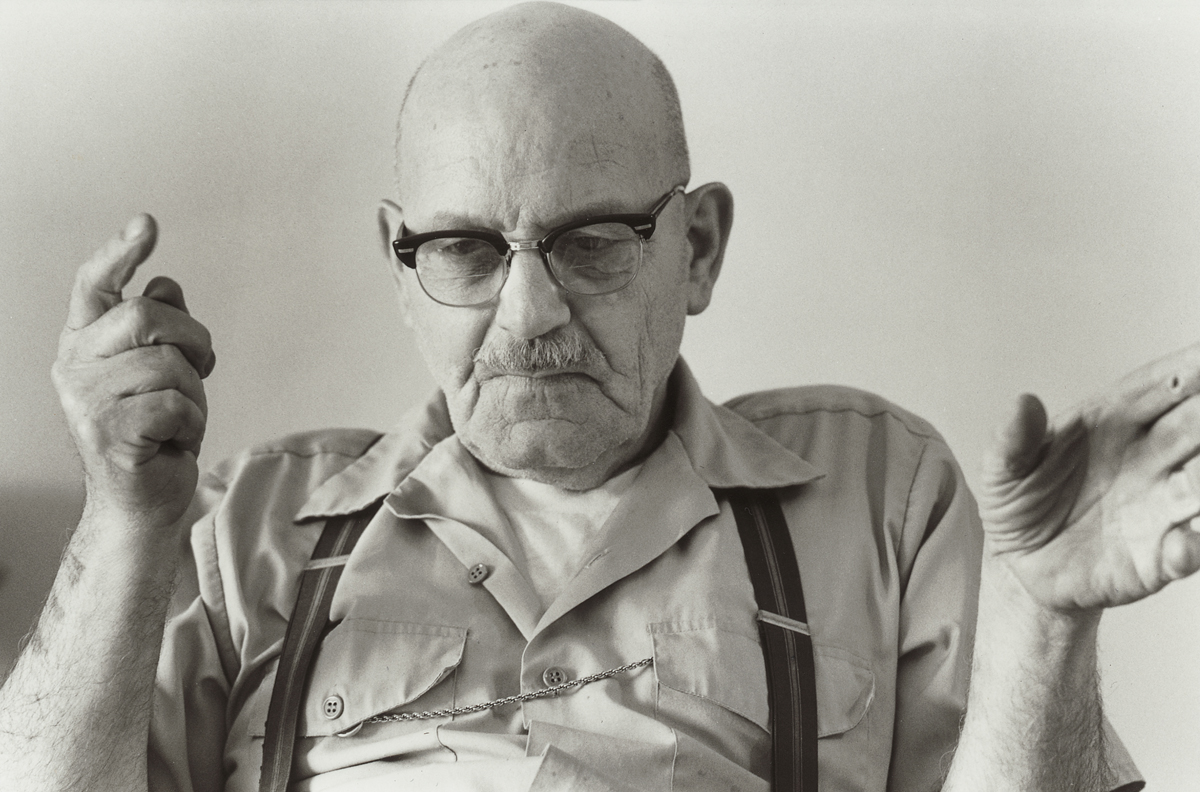

In the early 1900s, the Seattle waterfront was so busy, with steam schooners running up and down the coast hauling lumber, “you could get a job anytime,” said Jesse Petrich, retired seamaster. “A lot of the shipping was done out of the bars and joints on First Avenue. If anybody wanted a sailor and couldn’t find one, they could always go up to McDougal’s.”

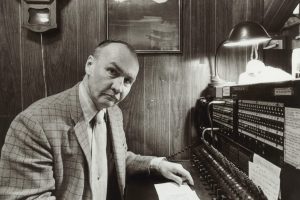

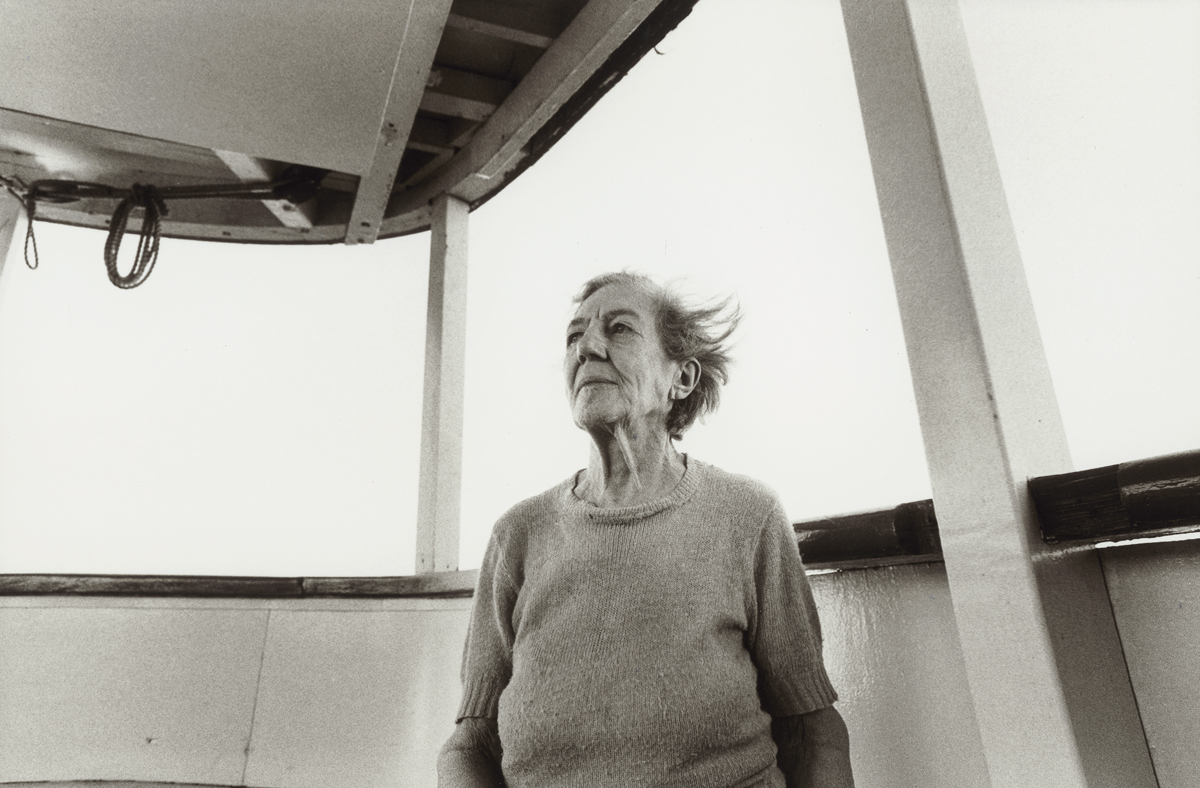

Leone Smiley, one-time pilot of a steamship called the Virginia V. “God, there must have been 22 steam schooners running up and down the coast hauling lumber,” said a former captain.

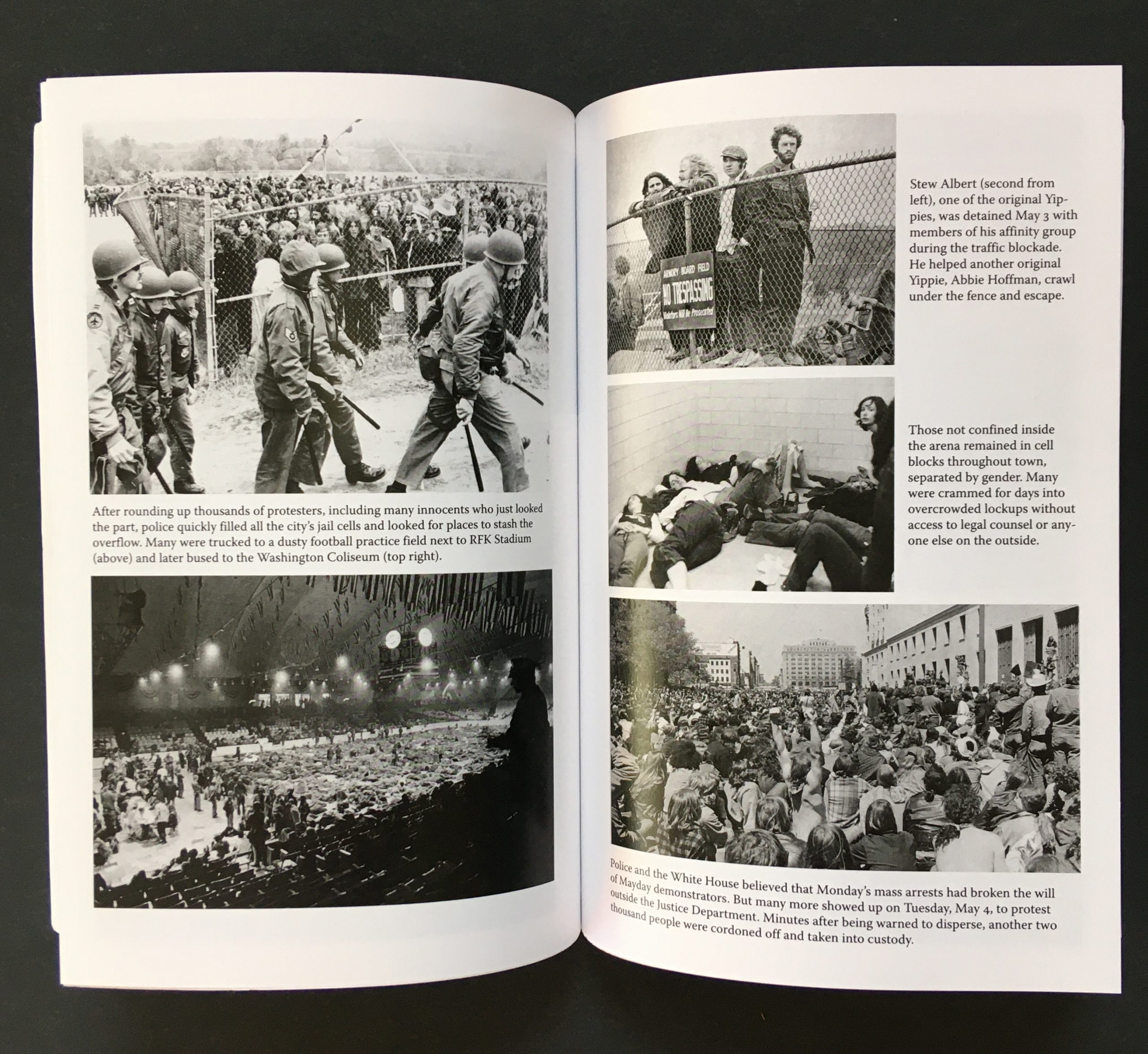

World War II brought boom times to downtown Seattle, but the military and civilian jobs faded away in subsequent years. The docks and warehouses of the central waterfront were replaced by a container port further south and you no longer could hire out as a logger from a tavern. Those left in the rooming houses and residential hotels were largely elderly and living on fixed incomes.

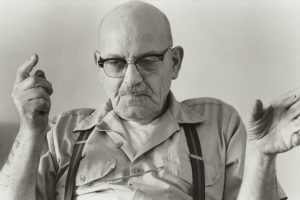

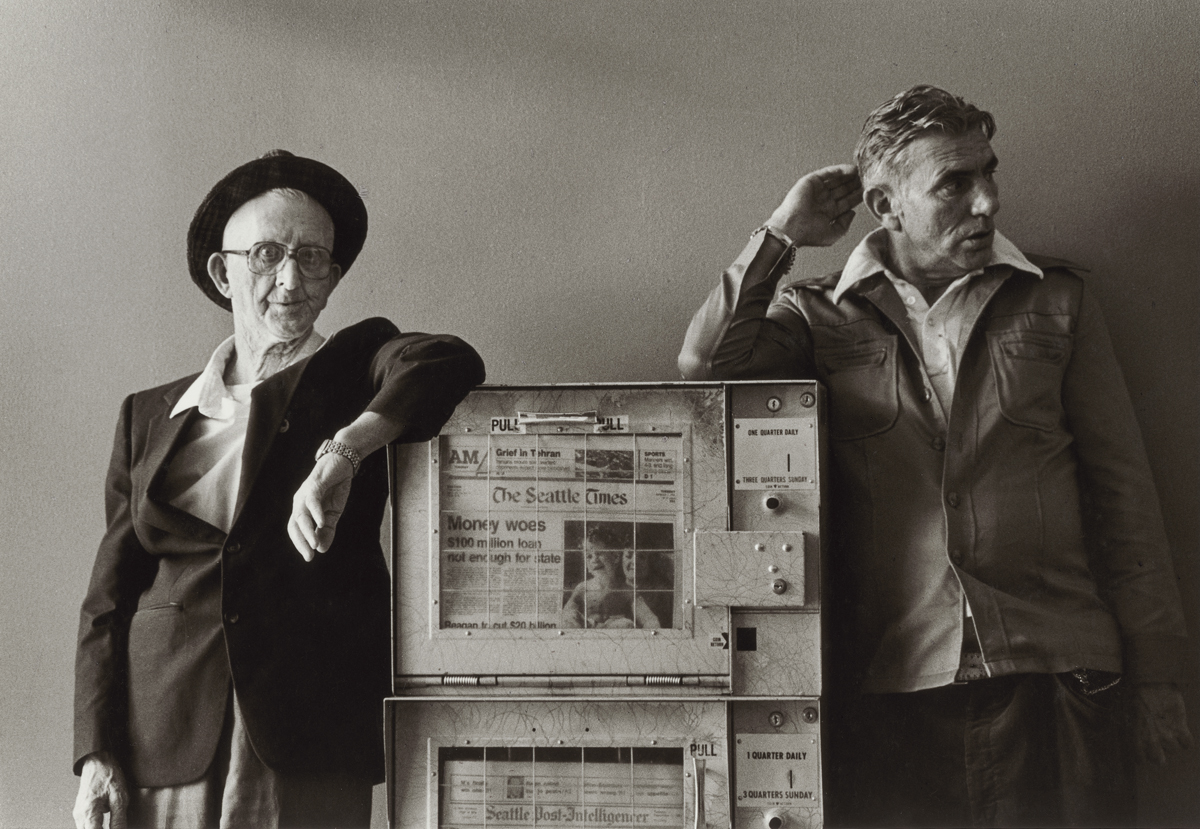

The Seattle waterfront in 1981. “In the 50’s there used to be 4,000 of us longshoremen. Now you’ve got two crane operators, six semi-drivers, two slingmen and four stevedores. They hardly ever see each other,” said Joe Wenzl, longshoreman since 1952.

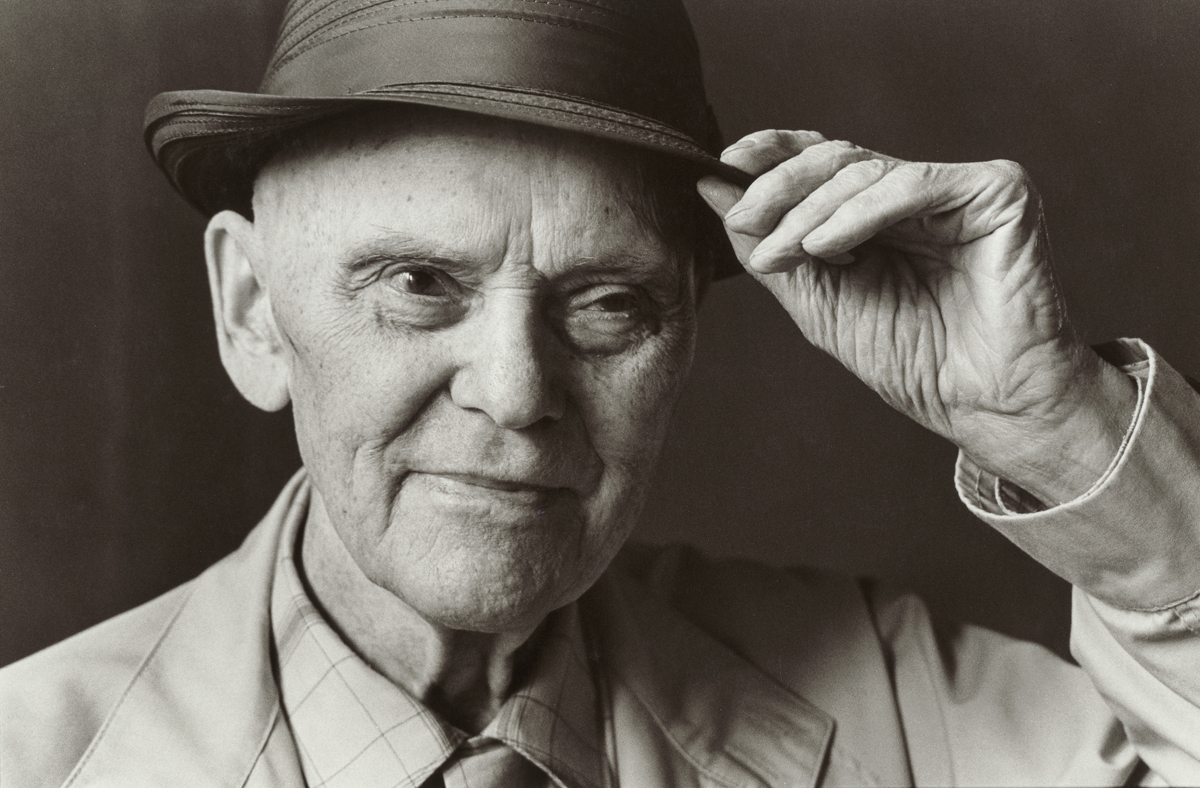

Along with houses of prostitution, the avenue became home to arcades with coin-operated machines to watch racy moving pictures. What passed for a dirty movie in the 1950s was pretty mild. The first time Frank Ottersbach, a former beat cop, raided an arcade and checked out the machine, he saw a scene of two girls sitting on chairs, one in her underwear, the other in a housecoat that would flop partly open a few times. “None of the garbage you see today,” he said.

The Turf was one of the older eateries along First Avenue. “This area is like a small town,” said Dizz Ward, the restaurant manager. “You can go five blocks down the street and start a rumor, and before you can get back here, the rumor’s already gonna beat you.”

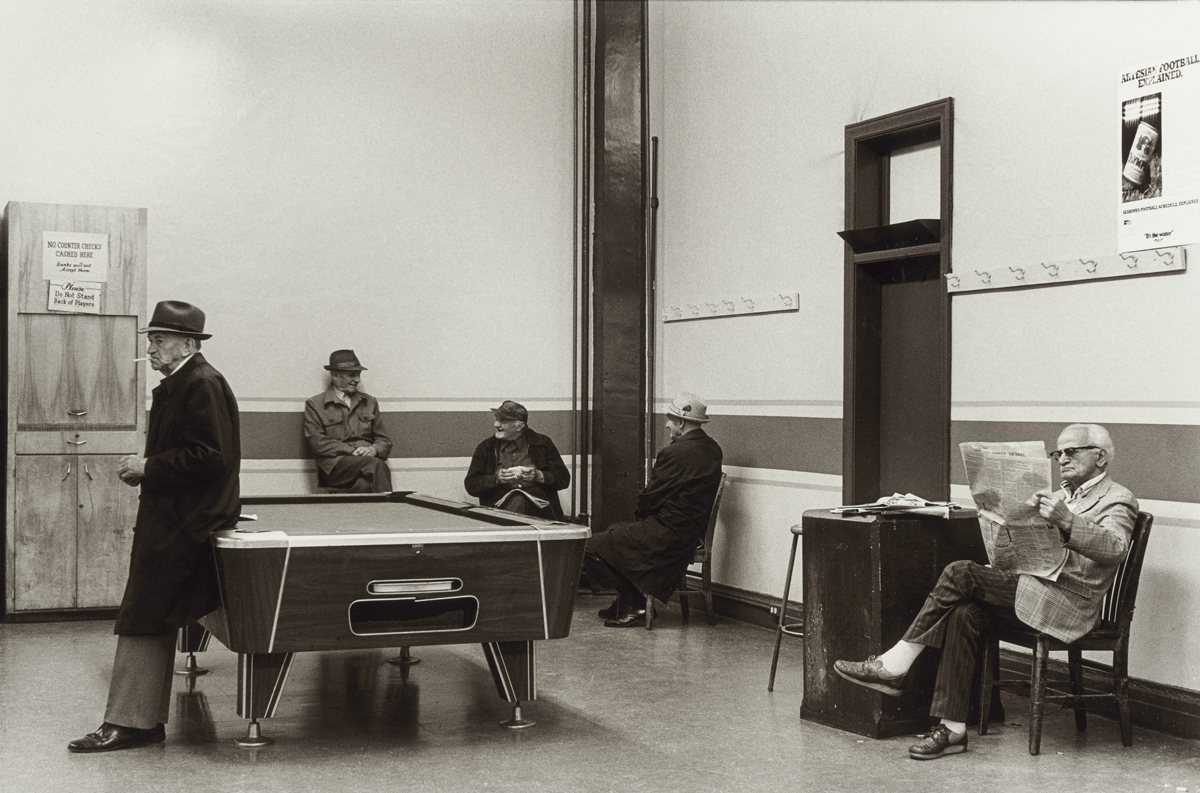

Old-time restaurants like The Turf served an aging clientele. “This is their low-rent club,” said Dizz Ward, the manager. “People come into the Turf at eight or nine in the morning and stay till eight or nine at night. Never walk out. They’ll have a snack or two, a bowl of soup, sometimes a meal. But this is where they’ll spend the rest of their lives.”

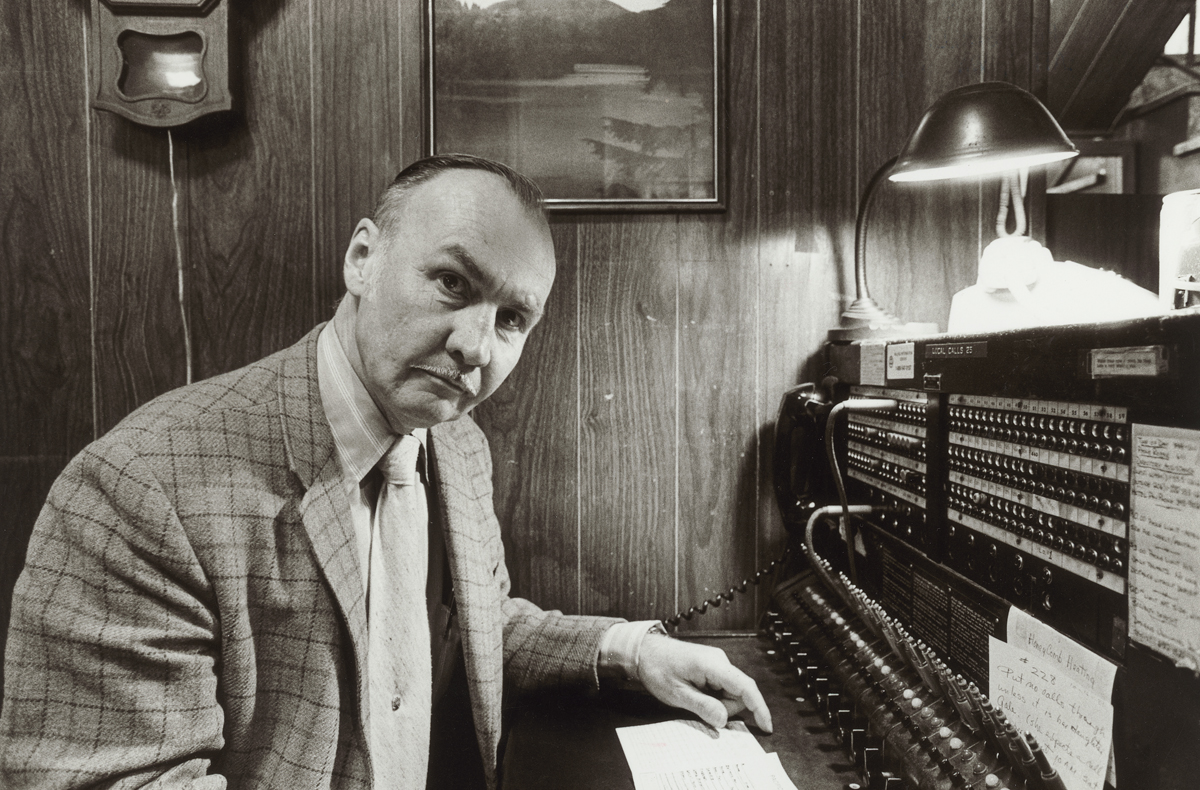

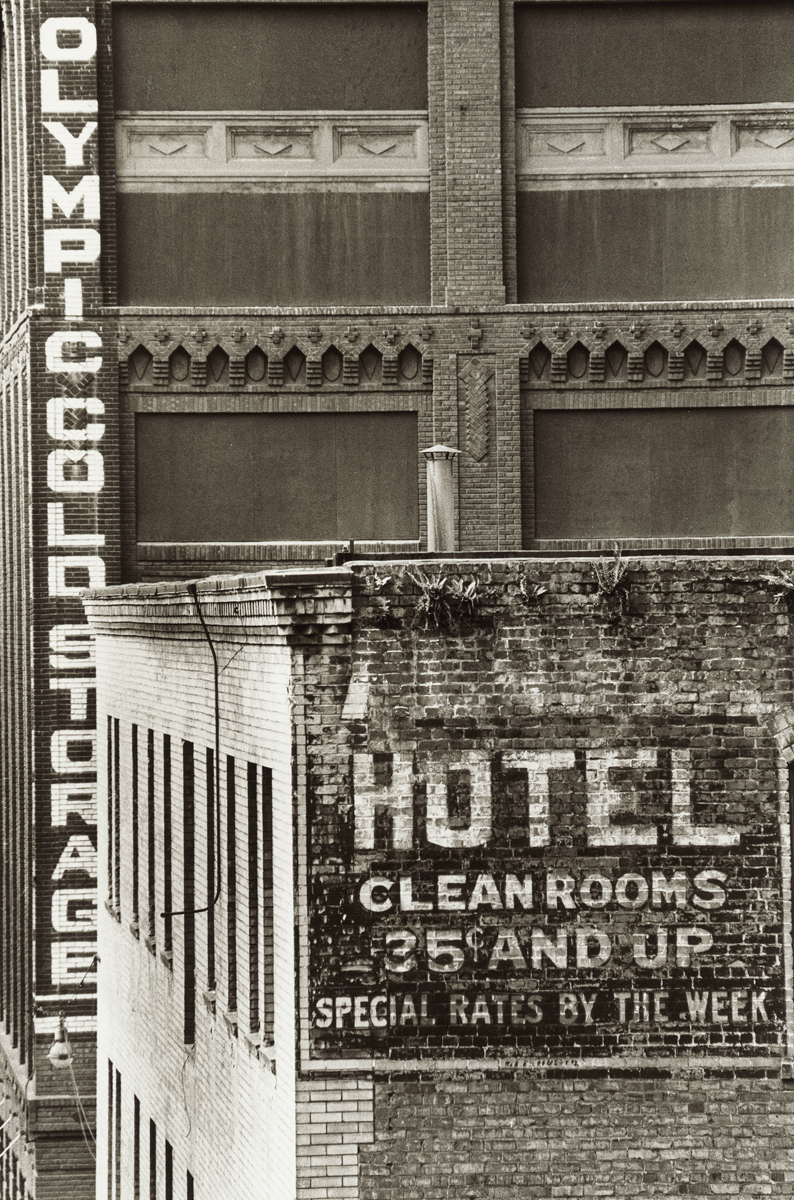

Some 15,000 units of low-income housing disappeared as downtown Seattle began changing again during the 1970s and early 1980s. One victim was the Gatewood Hotel at First Avenue and Pine, where Bob Grouse was the desk clerk. Residents paid $25 to $30 a week for a room without kitchen or bath.

The workingman’s culture on First Avenue used to revolve around the union halls. The dock workers had lots of options, since most also had experience on fishing boats or steamers. “At that time you didn’t give a particular damn if you got kicked off the waterfront,” said Joe Wenzl, a former longshoreman. “You could go sailing or fishing. There were jobs for a man with a strong back then.”

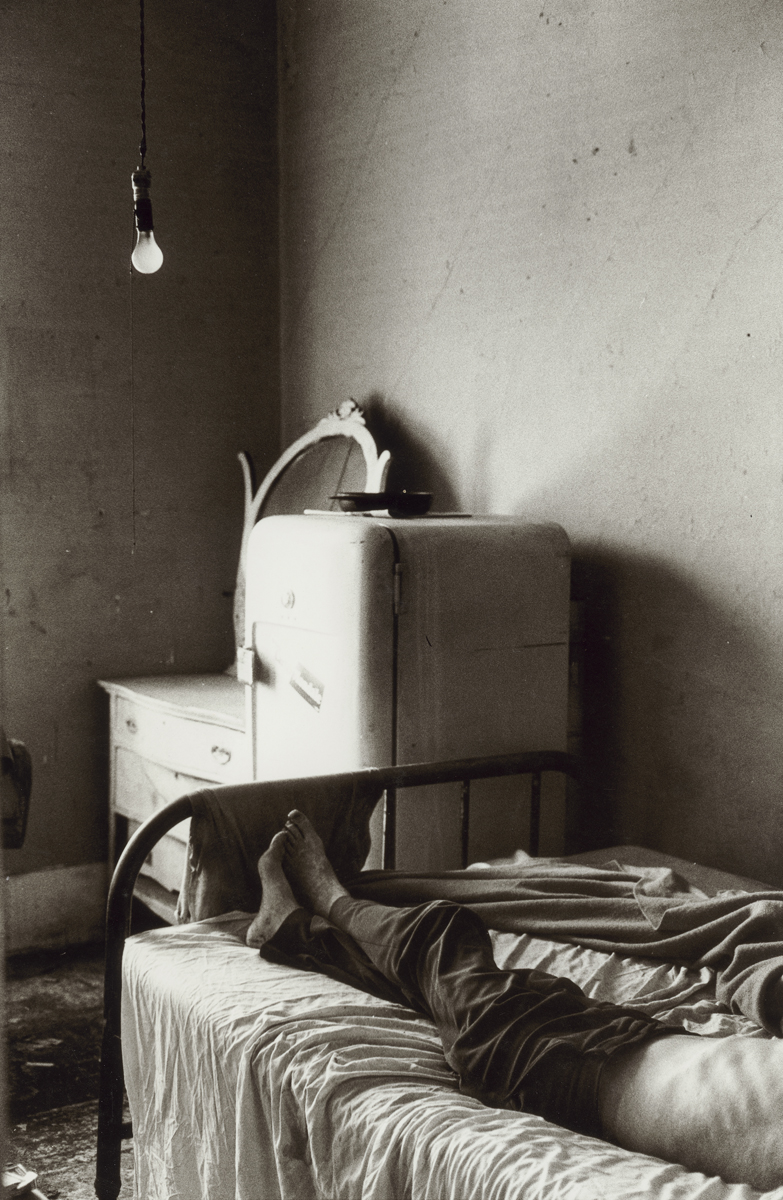

A room at the Oregon Hotel. “In the ‘30s and ‘40s there were mostly working people in the housekeeping rooms,” said Betty McCallister, a longtime First Avenue resident. “Your landlady considered you company. If you needed an extra potato because you had an unexpected guest, you thought nothing of going and asking her for a potato. People weren’t as secluded as they are now.”

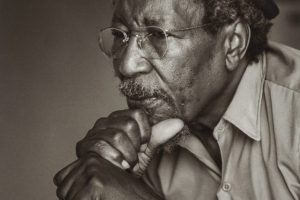

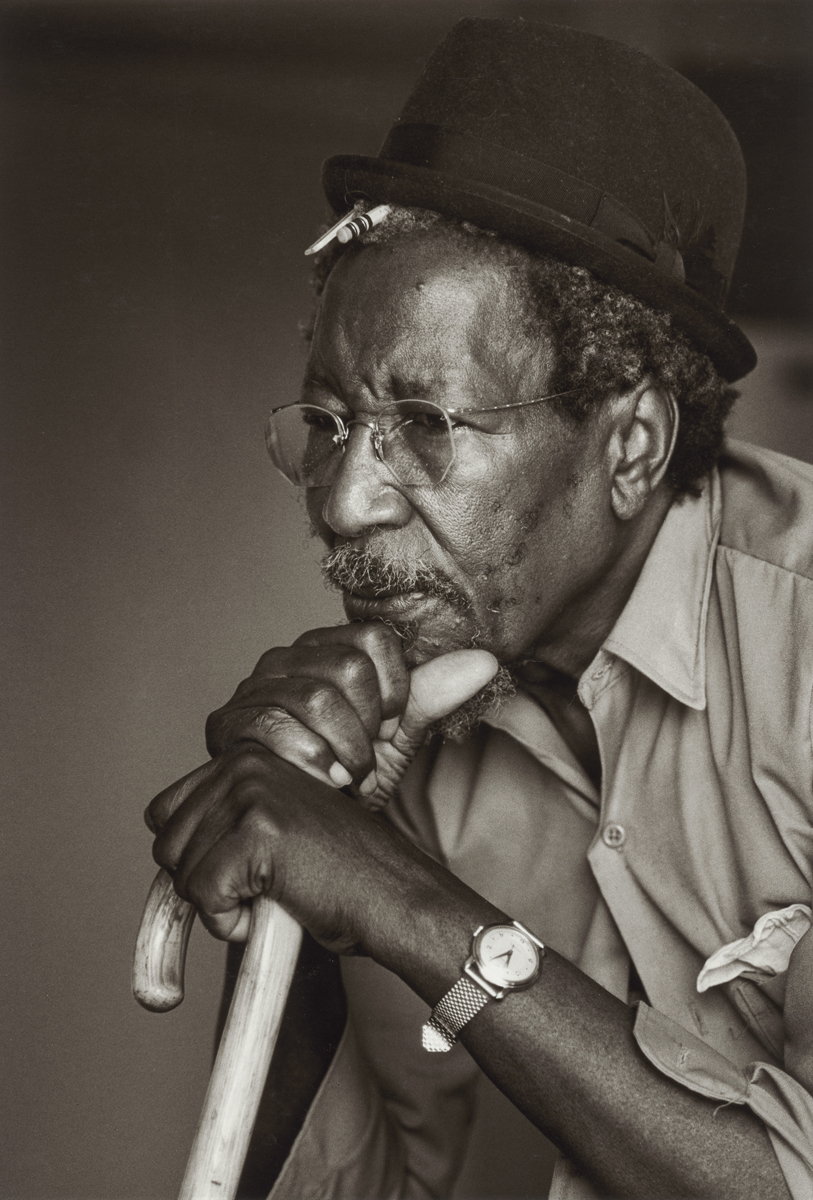

Maurice Beckles came to Seattle from France in the 1930s and eventually opened up the Spot-Nik Café. After it closed he lived in the La Salle Apartments, but always dreamed he could find a way to leave First Avenue. “I lived for the days when I could have had a permanent place,” he said.

First Avenue’s residents lived in some of the city’s cheapest housing with access to some of the greatest views. “You sit up on the hillside here and look out across Puget Sound, and on and on, all the way to China,” said Mac McCanlies, resident of the Livingston-Baker Apartments. “You have to look not only with your eyes but with your feelings, your smile, your atmosphere, your heart, even sometimes your touch.”

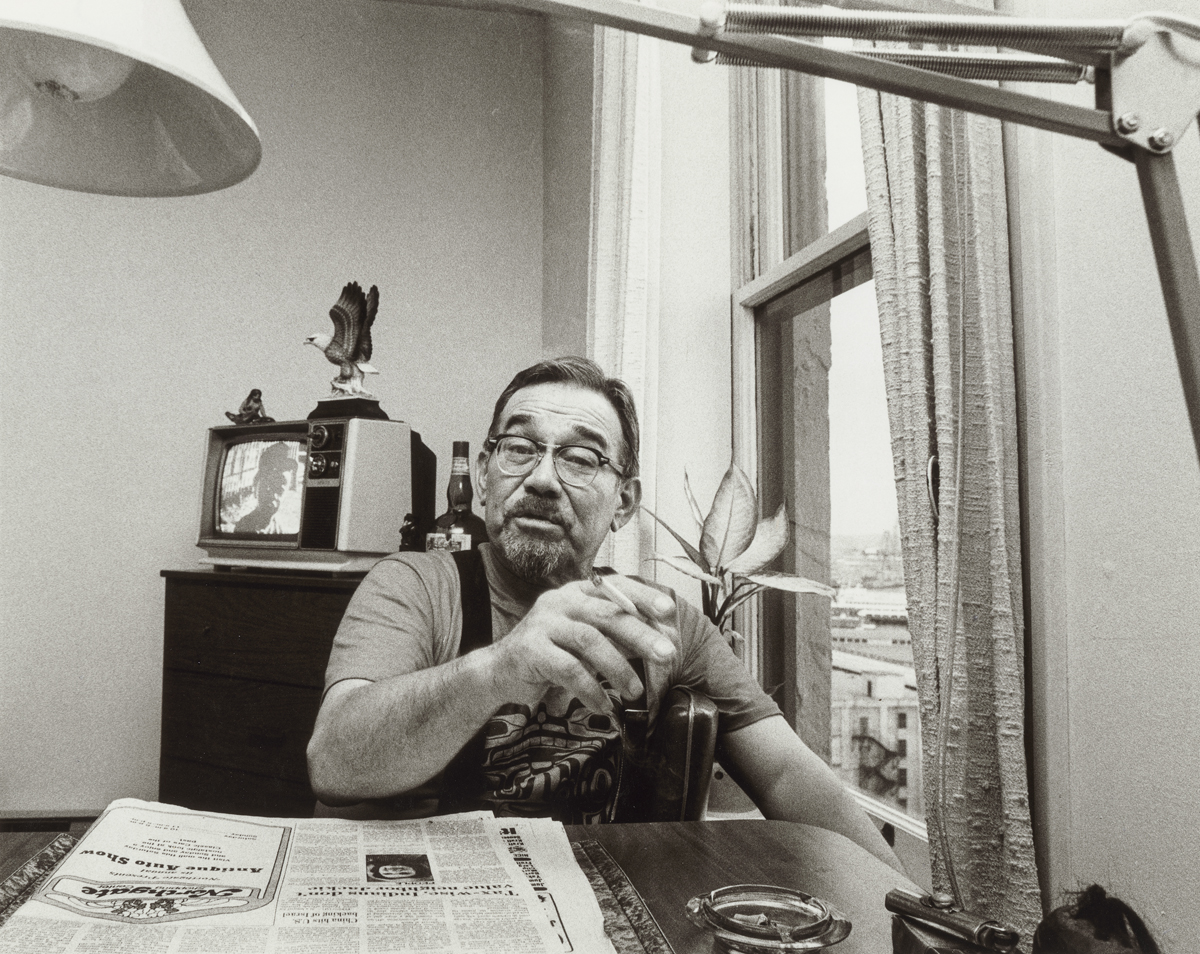

“I have ancestral memories sometimes,” said David Edenso, a native Alaskan Haida. His forefathers were traders along the Pacific coast before the white people came. His home was now the La Salle Apartments. “I can dream dreams of our coming to the Queen Charlotte Islands, and no one alive should be able to remember that.”

Early residents of the Lenora Hotel were workers or families temporarily down on their luck. Over time the housekeeping rooms were taken over by single men with little means and often no family. On holidays or birthdays, the hotel’s owner would send her daughter, Cathy Sumi, to knock on the doors with plates of food. But outside the hotel, Cathy hated to tell people where she lived. “You mean with all the bums and stuff?” they’d ask her. “They’d just give you this look, like, ‘You’ve got to be kidding.’”

The Sumi family, owners of the Lenora Hotel since 1956. “I don’t really care for the condominiums and so,” said Rosie Sumi (center). “I would have liked to see the neighborhood restored instead of torn down. Every window you look out now, there’s a big building towering over you.”

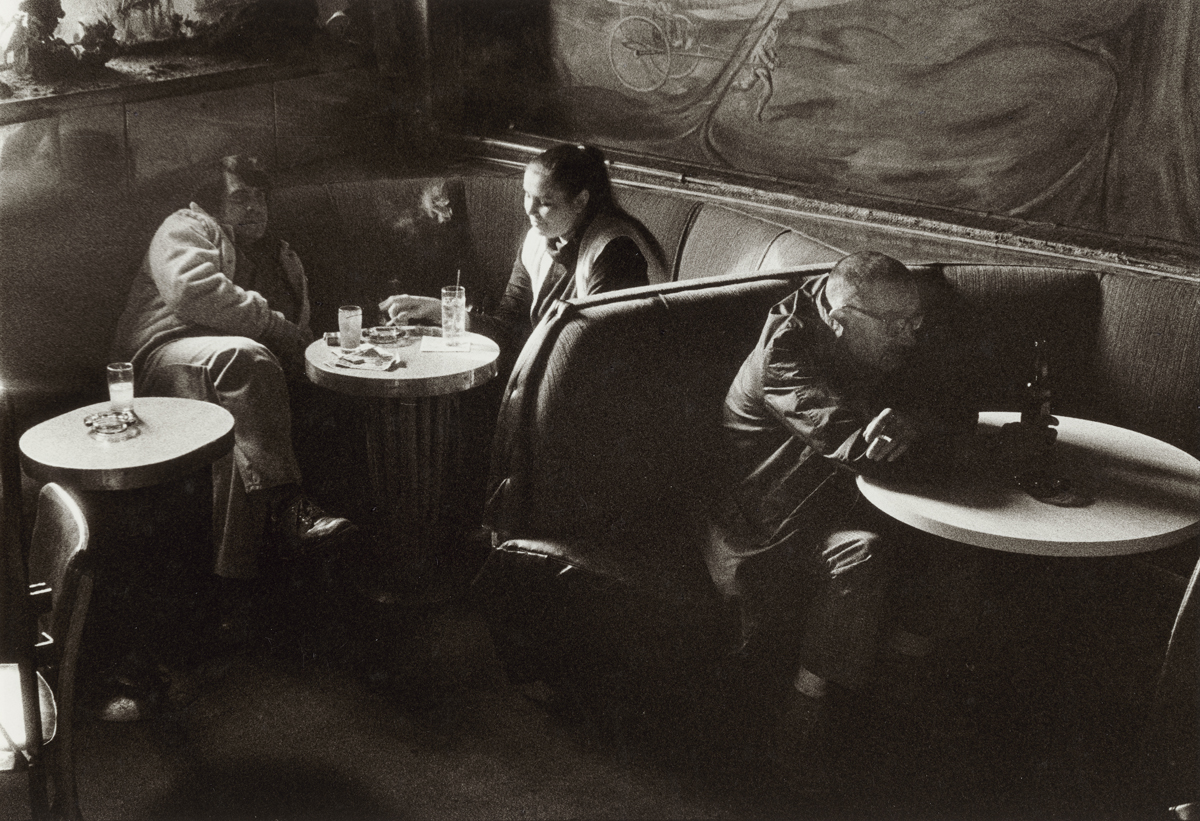

The bar at the Riksha Room. “Outsiders see this neighborhood, right away they say all you’ve got downtown is a bunch of winos, a bunch of drunks and a bunch of derelicts,” said Bob Grouse, a hotel desk clerk. “They don’t realize there is a good class of human beings that live downtown, that love to live downtown.”

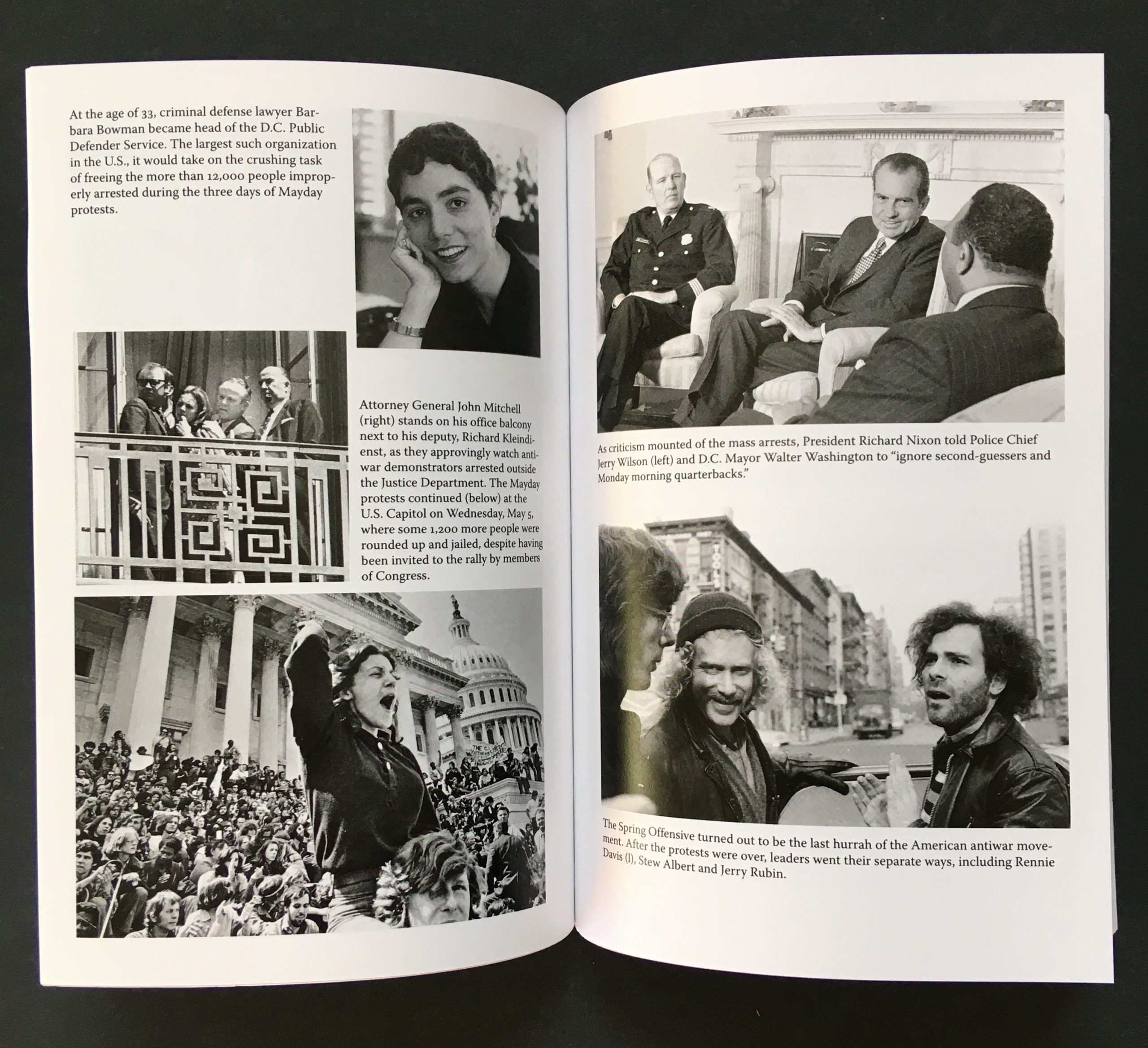

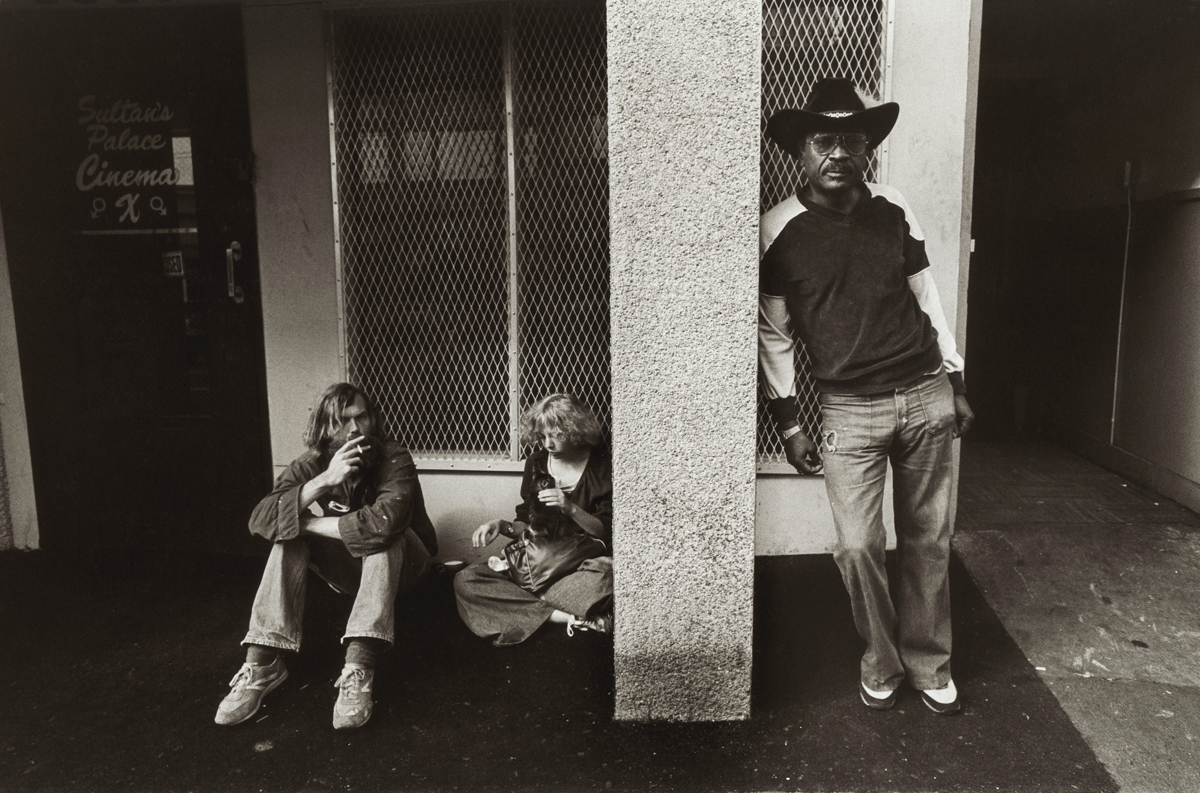

Richard Evans, in the cowboy hat, assistant director of the First Avenue Service Center. When he started in the mid-1970s, he saw relatively few homeless people, and they’d all but vanish in the summers, when seasonal work still could be found. That changed a few years later, he said. “A lot of the people who end up on Skid Road today are young. They tell me that they watch the six o’clock news back in Louisiana or wherever, and they hear that Boeing or one of the shipyards has a big contract. And they think, well, God, there must be work there. So they come.”

When the Gatewood Hotel closed and its 30 tenants were evicted, a disabled ex-waitress named Audrey Larson refused to budge for a month. “I begged the other tenants not to leave,” she said. “They said, ‘What are you fighting, Audrey? The establishment?’”

The window of the Riksha Room on First and Pine St. Many of those on First Avenue are cut off from family ties or friends. “The loneliness is the big thing here,” said Richard Evans, assistant director of the First Avenue Service Center.

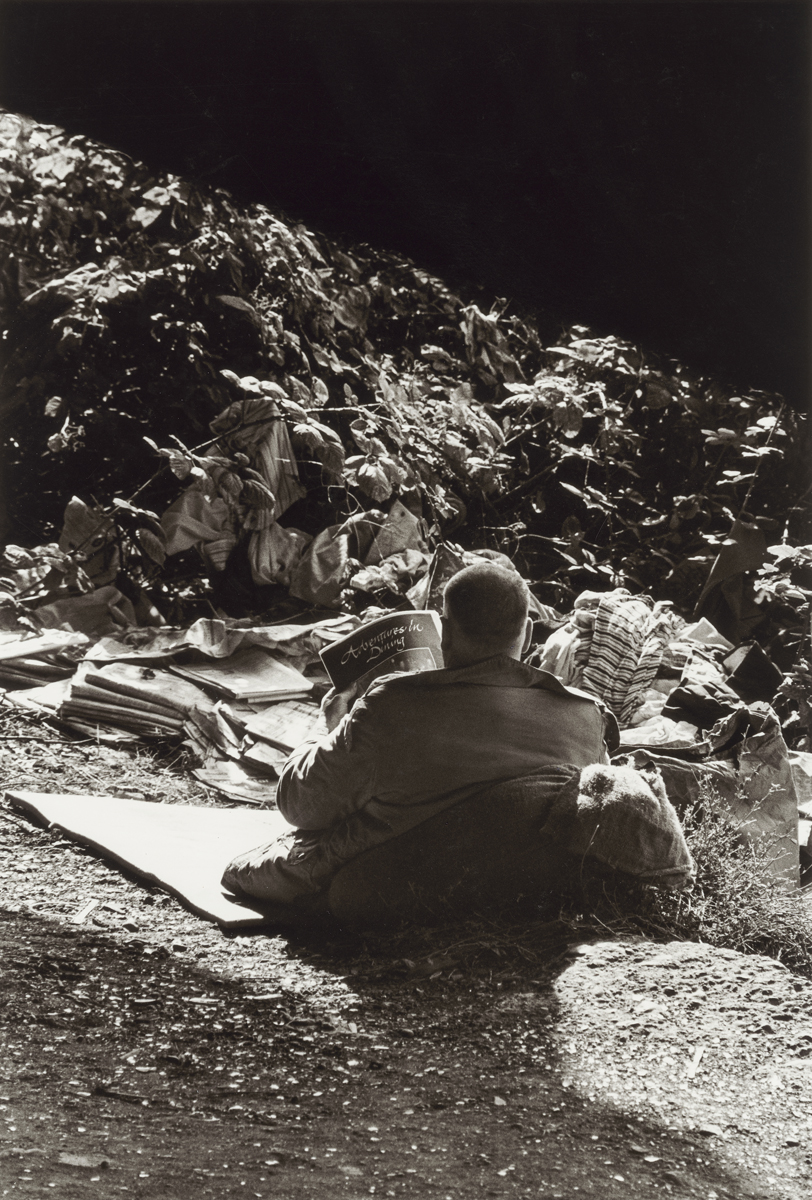

“It’s another world people don’t even realize exists,” said one First Avenue resident. “People live and work and travel apart from the normal work force, picking apples and pruning trees, working in labor pools. They sleep under bridges, in sewers and in missions. This is a whole different ballgame.”

A new condominium rises behind the Oregon Hotel and the Seafarer’s Tavern in Belltown. The long-standing residents of First Avenue couldn’t hope to afford the new housing. “You can go get one for 300 grand,” said Ken Crawford, a resident of the Livingston-Baker Apartments. “Right next to a low-income building like this.”

Ken Crawford, resident of the Livingston Baker Apartments at the Pike Place Market. “I have a pretty good idea where I’m headed. This life is just one miserable stepping stone,” he said. “We all get hung up in these little snags, but you gotta hang tough.”

“Even tourists don’t like things too artificial,” said Robert Stewart, resident of the St. Regis hotel. “Every city ought to have a place where all kinds of people can mingle. It’s spiritually healthful. Seattle always has had this and ought to hold onto it.”

“Where they try to create the atmosphere of the old Seattle, there is a distinct phoniness about it,” said Mabel Petrich, resident of the Sanitary Market Apartments. “Because the characters that created the atmosphere they want to shove under a rug, and they want them to disappear.”

Ruby Label, manager of the Frye Apartments, a historic hotel in Seattle’s Pioneer Square Area which provided affordable rooms.

Waiting for the senior center bus after grocery shopping. “I think the only safeguard for the senior citizens is for the community to become aware of keeping us here for the color and the down-to-earth feeling that even tourists like,” said Robert Stewart, resident of the St. Regis Hotel.

The counter of The Turf restaurant. “You start reminiscing, remembering people who’re long dead,” said Dizz Ward, the manager. “There’s some lies in there, and some reality.”